For many architects, a project will present up to seven phases of design. Once considered an integral part of this process, modelmaking has increasingly been sidelined due to competing technology and shortening timelines. Associate Director David Brooks – one of Carr’s modelmaking advocates – discusses why the craft is the most honest device within an architect’s toolkit.

Take us back to the beginning of your modelmaking journey. When did you first delve into the craft and why?

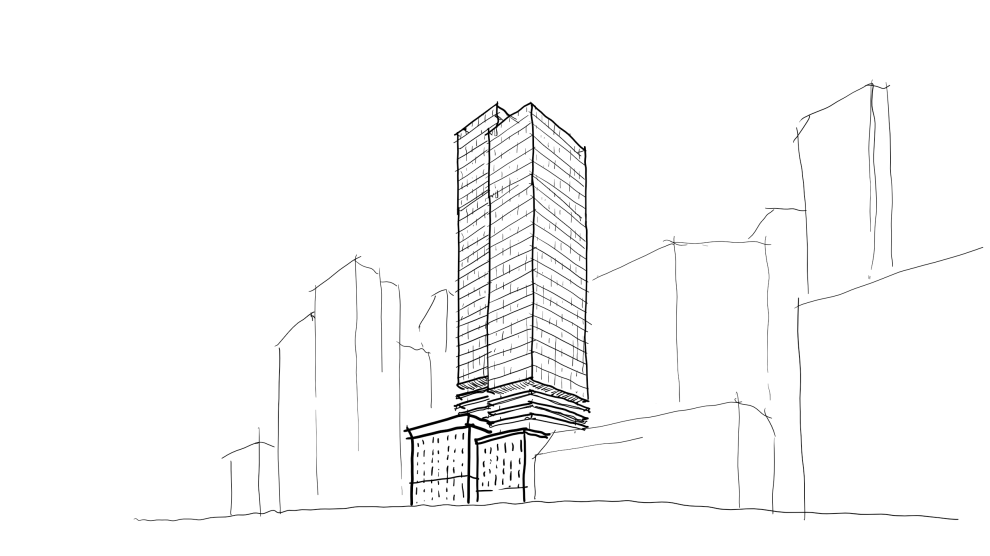

I was first introduced to modelmaking in university. It’s the ‘making’ of architecture that I’ve always enjoyed and seeing how things go together, so this was an illuminating experience for me. Models are an easy way to visualise and resolve problems. So much so, that it is still implemented when I do full-sale master planning and large-scale buildings today at Carr.

Renders are regularly used to provide a snapshot of the completed project. How do models enhance the Carr process beyond computer graphics, considering that renders are known for their relatively quick production and aesthetic appeal?

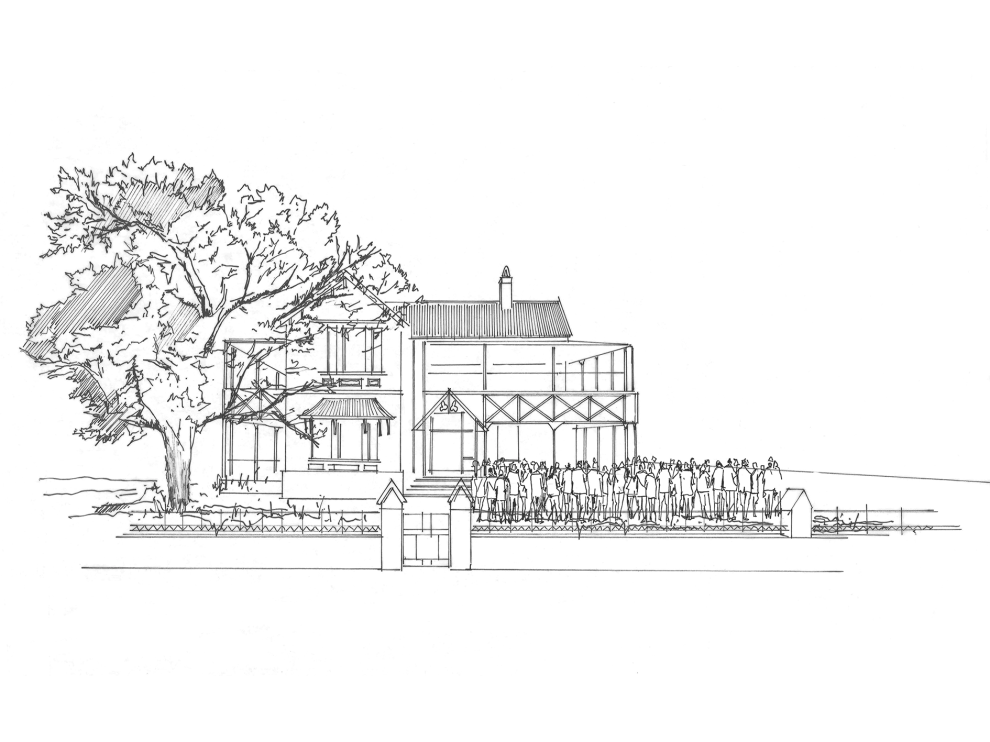

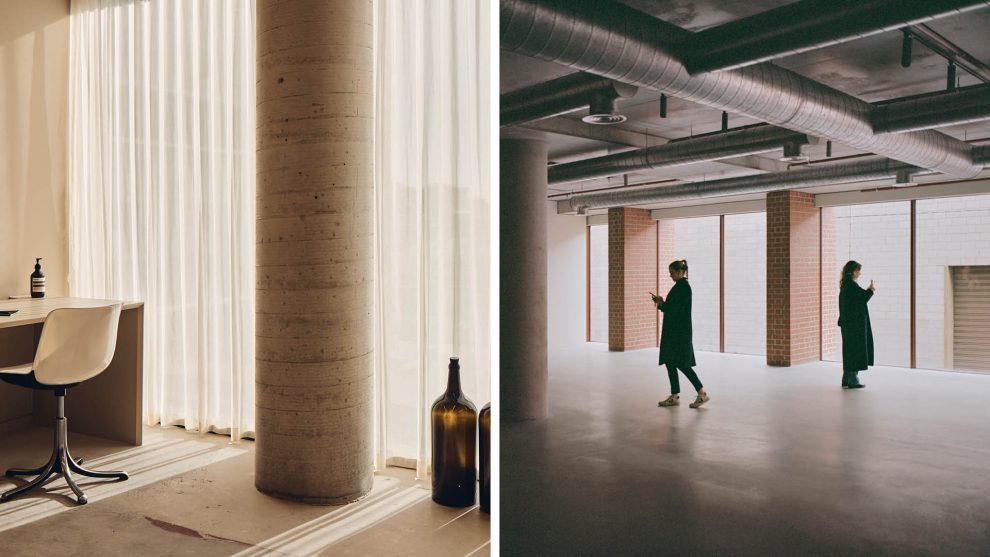

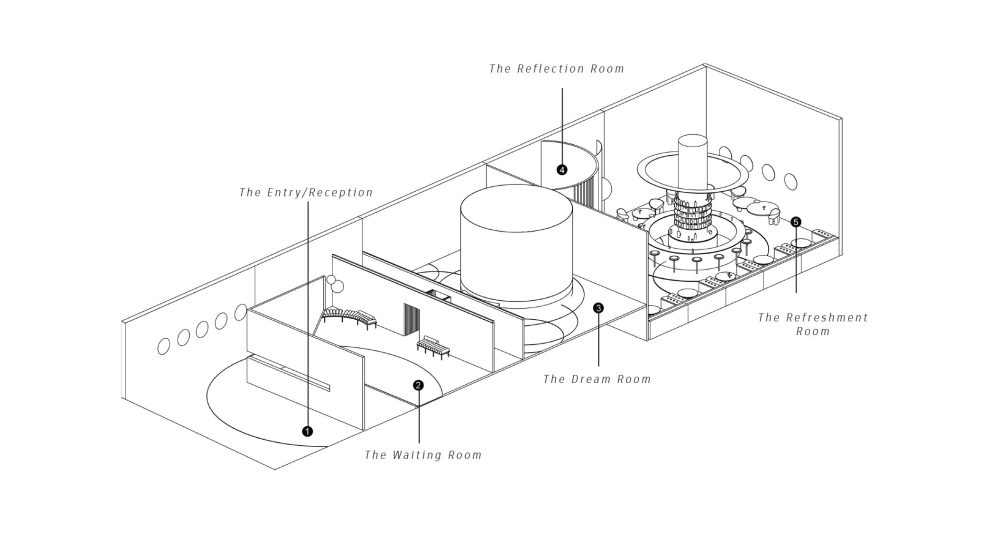

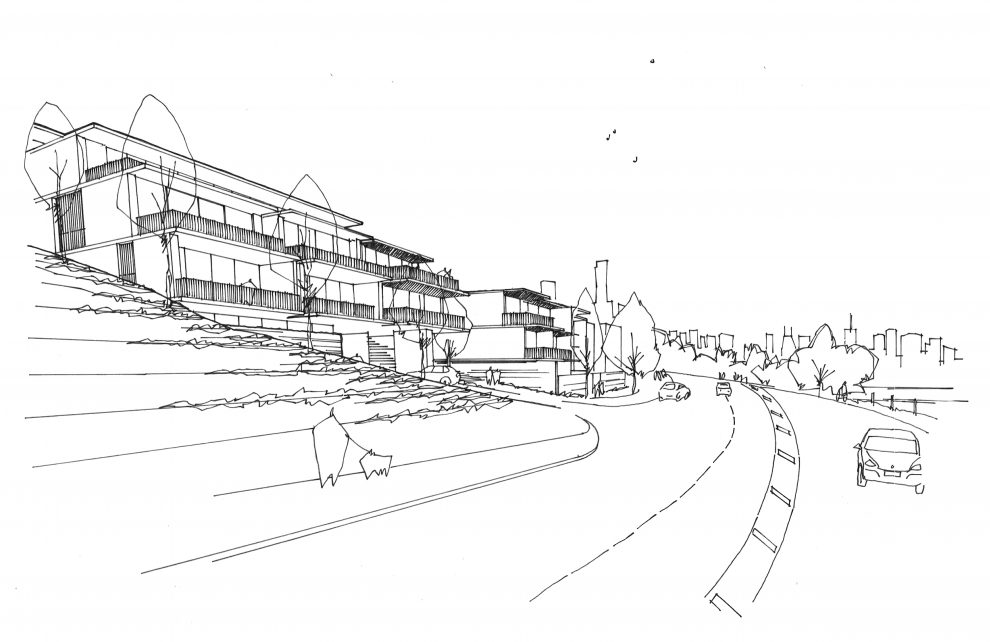

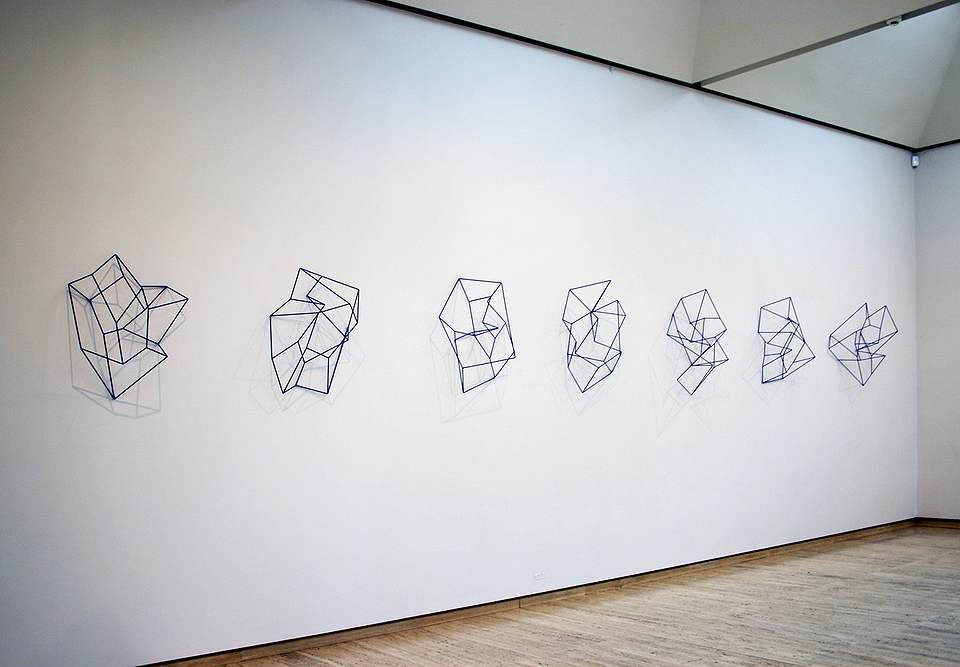

There are three main forms of representation in architecture – sketches, models and renders. While renders create beautiful and emotive imagery, they can warp reality. Models, however, let you see a building in a particular honesty and simplicity that avoids distractions. And because models are far more elemental – as in, you must manually build them – they become an extremely satisfying exercise.

At Carr, our process involves developing the design to a level of detail that’s represented in computer graphics. To create the model, we break down the design into simpler parts to effectively communicate the key ideas. Through this process, we gain a deeper understanding of what works and what doesn’t. The model shows proportion far better, exhibiting true light, shade and scale within a built form. While renders are powerful, due to their capacity for manipulating ambient lighting and focal lengths, models leave nothing to be concealed.

What do you personally enjoy about modelmaking beyond the technical aspects?

I get a great deal of joy in modelmaking and love seeing the project come to life with the team. There’s a certain amount of guarantee you’re going to achieve a compelling image from it. You can see that coming along the way, but to see it in its physical form is second only to seeing the project built.

While models are still implemented during the design process, particularly for large-scale projects, they are now considered more as an additional tool rather than a necessity. Do you think this means modelmaking will become a dying art?

Yes, I think so. At least as part of the architectural process as it takes time. With condensed timeframes, increased emphasis on planning processes, holding costs on sites, and client uncertainty, the buffer in the program for models is being removed.

Once we achieve a certain level of stability in the design process, we can then fabricate the model. But I hopefully think for models to serve their intended purpose, there needs to be a shift away from the concept of ‘fast food architecture’, where the expectation is to rapidly produce results solely due to technology, without dedicating the necessary thought, testing and research.

I think it would be a shame if models were to become obsolete. They are an extremely useful and enjoyable learning tool that I have relied on since my university years.

At Carr, we aim to make our clients feel part of the creative process on all our projects. Why do you think clients particularly enjoy seeing an interacting with the models?

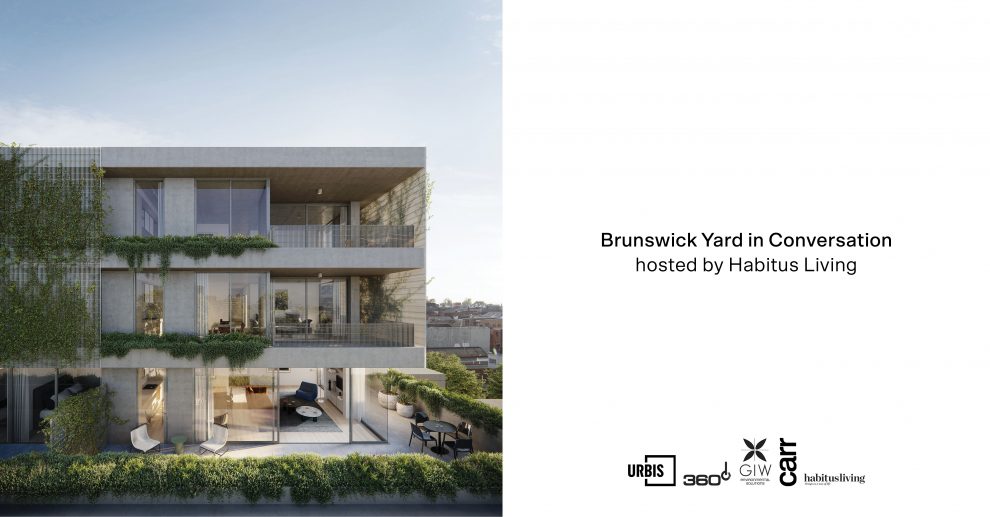

Not only does it give them certainty of what the project will look like in reality but it’s also useful to show colleagues and other investors. Models have universal appeal. People understand them!

Models also help promote the project to potential buyers as well as streamline the planning process. If the model can be used to smooth or reduce the timeframe of that phase, then that is a great asset for the client.

Significantly, the uniqueness of models lies in their ability to capture the intangible moments. They evoke a deep sense of nostalgia – something renders often find challenging to reproduce.

Why do you believe it is important for young designers to be involved in modelmaking?

One of the fundamental skills vital for young designers is understanding how things come together in terms of constructability.

There is very much a creative element in working with what tools you’ve got, each limited by materials and time pressures. There are three different techniques we use on models – CNC router, laser cut, and 3D printing – which include powder and resin. All produce different textures, levels of detail and outcomes. It’s important to know the benefits and challenges of the materials and how they come together to represent an idea – akin to constructing a full-scale building.

These learning experiences are precious and intrinsically rooted in the craftsmanship of modelmaking. They are not simply inanimate ‘models’ but storytellers of a project’s proportion, personality, and purpose.

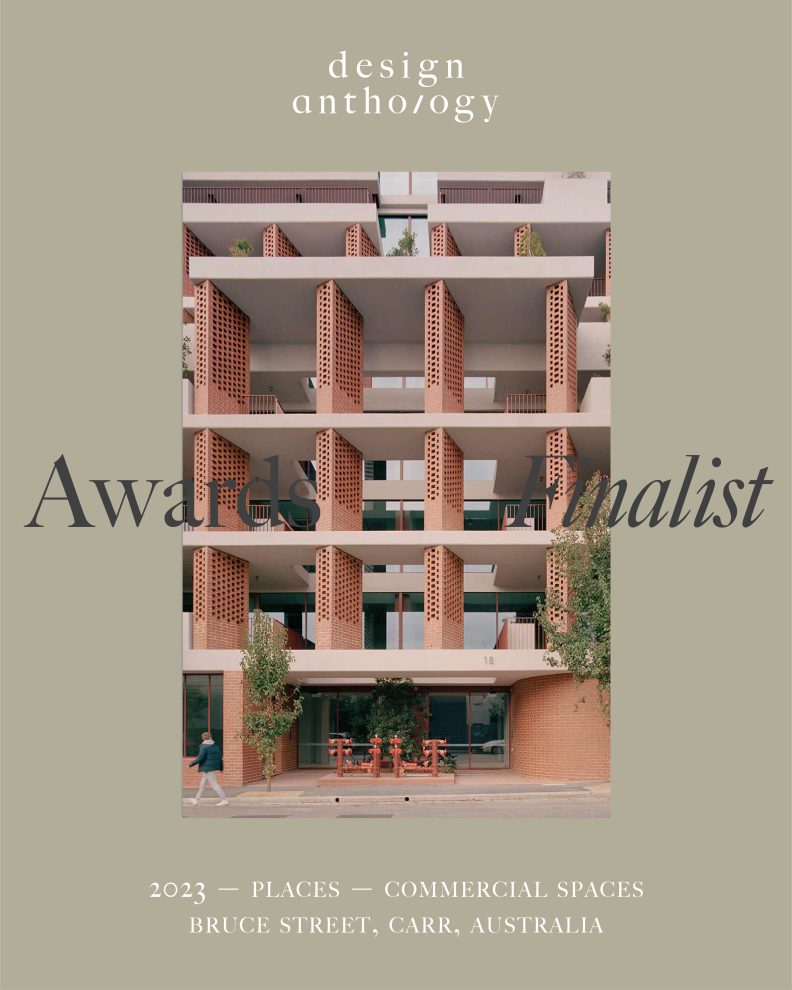

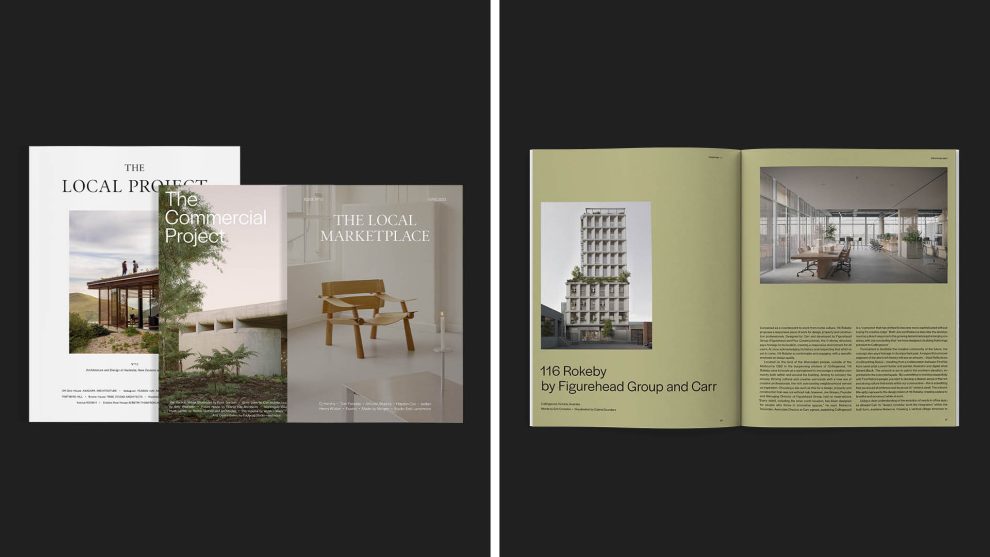

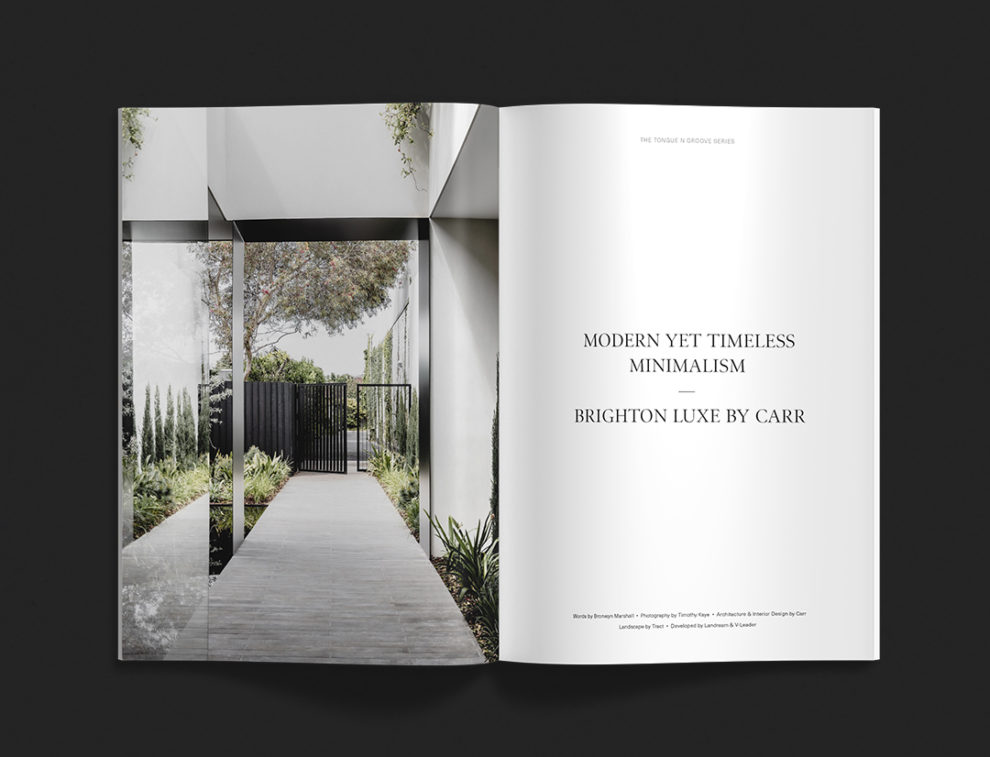

Explore how the proposed design of 623 Collins Street looks to its historic surroundings for its architectural inspiration, seeking to engage with the existing site, its context and character.